As I've fiddled on this old rifle, I've found that most of the forward steps I've made have revolved around the transition between the case and the barrel. Having the bullet all the way out touching the rifling, having a heavy enough bullet to deform under load, having a soft enough bullet, all focus on the short distance where the bullet is leaving the brass and entering steel. This got me to thinking, and measuring, and I quickly determined that my chamber is a fair amount longer than my cases. This isn't a huge concern for a military type gun, since the case is held by the rim, but it seems a good avenue to play around with.

I picked up a product called Cerrosafe, which is basically a low melting point solder. It is used to make castings of gun chambers so you can take a look at the shape. This is especially useful for the trapdoor where the breech is all shouded and you can't get measuring tools in there. You just plug the barrel with a wad, heat the Cerrosafe with a small torch or hair dryer and pour it in the chamber. Be sure the ejector cutout doesn't fill in, or it will stick in there. Also, be sure the wad isn't too deep or the plug will be too long to get out the breech opening. Once it cools, it taps out with a cleaning rod.

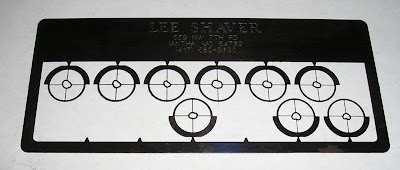

Here's a photo of the plug:

In the center is the chamber casting. As you can see, it was a bit cold and has folds, but it gives me the info I need, so I never remade it. The brass on the right is one of my 45/70 cases. The brass on the left is a 45/90 I got for this project. What's a little hard to see in the photo is that the chamber runs straight past the end of the shell, then starts to radius in, then hits a firm chamfered taper to the rifling. The goal is to trim back the 45-90 case until it fills the straight part of the chamber, reducing the distance the soft lead bullet travels unsupported.

WARNING - If done incorrectly, and especially with jacketed bullets, this can blow your gun up. The mechanism is this: If the case is too long, it rides into the radiused part of the chamber and acts like a crimping die, crushing the case onto the bullet. Normally, this is no big deal, there are overcrimped shells shot all the time. The trouble is that the chamber is still holding the crimp down when you fire, giving the case nowhere to expand to. Pressures go to the moon, as do gun parts. The solution is that the cases have to fit right, not too tight.

After measuring and trimming, I had 20 rounds where the cases were long enough to cover all the lube grooves. At the same overall length, my regular cases leave a lube groove hanging out. So, how did it work? Measurably worse. My horizontal variation went from a standard deviation of 2.2 to 2.9. Vertical was better at 2.0 going to 2.1. Oh well. Even knowing what NOT to do is still knowledge. A perverse part of me wants to try shorter cases. It seems to be the logical direction based on the data, even if it looks odd.

One good thing I got out of my day at the range was a well managed comparison of my prone shooting to my standing. While obviously my standing (offhand) groups are much larger, they also center in a different location. I've just never measured it before now, because it takes a fair effort tabulating hole locations, and I'm lazy. The data is in, and I shoot about 1/4" to the right and 2" low when I shoot offhand. Now I can think back to all those shots just under the chicken's feet and pretend to myself that they would be hits. That makes today a happy day, free from my tortured chamber.